Have you read Erik Larson’s The Splendid and the Vile yet? It’s about British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s leadership of his country during the Blitz air bombings of 1940-1941 – a time of great threat and uncertainty. The threat was the strong possibility of a successful invasion by Nazi Germany. The uncertainty was how long Britain could resist Germany on its own, with insufficient weapons and too few allies.

Today, almost exactly 80 years after the Blitz began, neuroscientists have learned a great deal about how our brains function under uncertainty and threat. They and other researchers have identified the leader behaviors that can help us replace fear and despair with “courage, cheerfulness, and resolution,” as a British war poster put it.

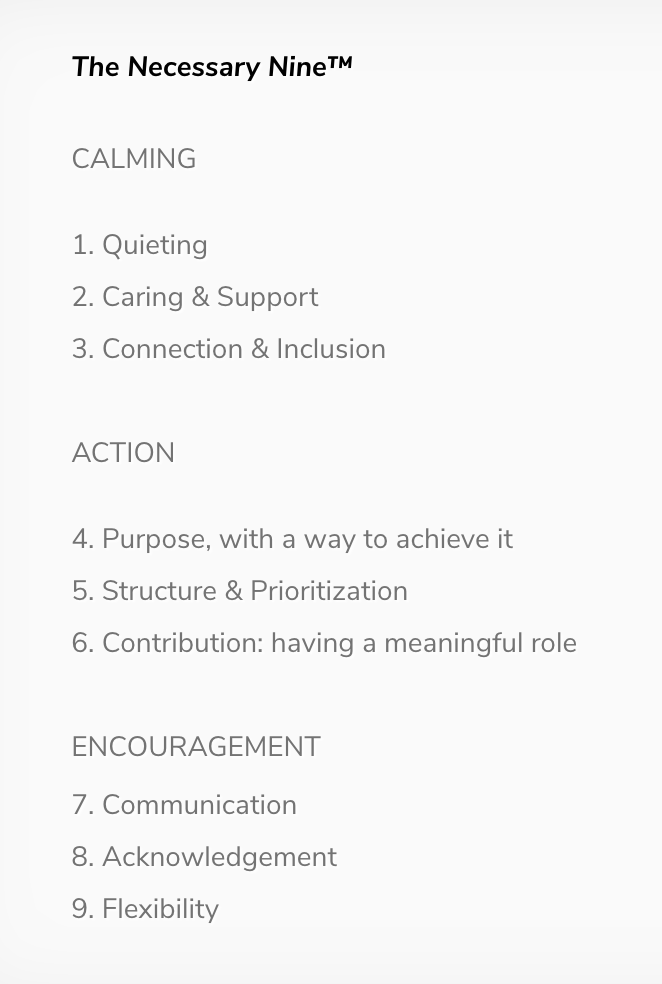

Rich Mayhew and I have summarized those evidence-based leader behaviors as the Necessary Nine™ behaviors for leading in times of uncertainty and threat, and we’ve grouped them into three outcomes: Calming, Acting, and Sustaining. These actions work in any role, from individual contributor to middle manager to Board Chair. As England’s Prime Minister in World War II, Winston Churchill used all nine.

Churchill was not a perfect man. Far from it. But he did much to calm anxieties, to ensure the country was acting on the threat, and to sustain people’s commitment. A decision he made for the fifth night of the Blitz represents what leaders must sometimes do to create reassurance when people feel threatened and uncertain — even if the action is impractical and wastes scarce resources.

Here’s the story.

September 7 the Blitz began as German planes bombed Greater London and continued to do so for 57 consecutive days and nights, resulting in over 13,000 civilians dead and nearly 20,000 injured. (As percentage of population, this death rate was 37% higher than the Covid death rate in New York City in its first 57 days of reported Covid deaths.) Brits couldn’t know it then, but the Blitz would continue months longer, into May 1941 – with still no official involvement from strong allies. How did the British stand alone for so long, until Russia and finally the United States joined in 1941? The fifth night of the Blitz bombing was one of the factors that made a difference.

For the first four nights of bombing, London seemed undefended, leading to morale collapse. Anti-aircraft guns were mostly silent, for practical reasons: they were ineffective against high-flying bombers, and ammunition was too limited to waste. Royal Air Force fighters, effective in the daylight, lacked air-to-air radar necessary for locating and intercepting enemy planes in darkness and had little effect at night. German aircraft attacked without noticeable resistance.

On that fifth night, September 11, 1940, the visibility of resistance changed. Churchill had moved additional anti-aircraft guns into London, more than doubling the number to nearly 200. He ordered their crews to fire freely, despite his awareness that they were unlikely to down enemy planes. As Larson describes that night, “Crews blasted away; one official described it as ‘largely wild and uncontrolled shooting.’ Searchlights swept the sky. Shells burst over Trafalgar Square and Westminster like fireworks, sending a steady rain of shrapnel onto the streets below, much to the delight of London’s residents. The guns raised ‘a momentous sound that sent a chattering, smashing, blinding thrill through the London heart . . .’”

In truth, the guns had little effect on the air raid and its damage. The real effect, as Churchill had anticipated, was on British morale and willingness to continue resisting Germany. Larson quotes Churchill’s private secretary’s September 12 diary entry: “Tails are up and, after the fifth sleepless night, everyone looks quite different this morning – cheerful and confident. It was a curious bit of mass psychology – the relief of hitting back.” Larson also quotes the next day’s Home Intelligence reports: “The dominating topic of conversation today is the anti-aircraft barrage of last night. This greatly stimulated morale: in public shelters people cheered and conversation shows that the noise brought a shock of positive pleasure.”

Larson credits Churchill’s “gift for understanding how simple gestures could generate huge effects.” Having survived the first few nights of horrendous bombing and damage, and now hearing the anti-aircraft barrages as immediate evidence of full resistance, Londoners adopted a “cheerful attitude on their belief that from that point on they would not die.”*

Churchill’s actions illustrate the Necessary Nine™ in use. With the impractical, resource-wasting decision to increase anti-aircraft action, Churchill quieted concerns about inaction, showed that the government cared enough to try to protect people, gave nightly reminders of purpose and ways to achieve it, communicated without words, and showed flexibility in meeting people’s needs.

If you want to test all Necessary Nine™ behaviors against many more examples from the Blitz, do read Erik Larson’s excellent book, The Splendid and the Vile. (I suggest buying the hard copy, so that you can make notes in the margins.) If you want to know more about the Necessary Nine™ and how to use them to cope with today’s uncertainties and threats, email or call us. You can also learn about our workshop Leading Within, Through, and Out of Uncertainty, at https://learningzenith.com/training-products .

____________

*This phrase is from Rich Mayhew, who described his own family’s experience: “My grandparents, whose London East End house was bombed later in the war, yet they survived huddled in the back, told me that after that happened they felt almost exhilarated, as if they were bulletproof.”